- Home

- Stephanie Greene

Queen Sophie Hartley Page 2

Queen Sophie Hartley Read online

Page 2

With a tremendous sigh of satisfaction, Sophie stuffed her socks back in her drawer. Making lists was another thing she was good at. No other member of the family was as good at it as she was. In fact, there wasn’t another list in any other underwear drawer in the house.

Sophie knew, because she’d looked.

Any list that wasn’t worth hiding in your underwear drawer wasn’t worth reading, she told herself firmly. She went down to dinner a happy girl.

Chapter Two

But after a quick glance at Sophie’s upturned face, all Mrs. Hartley said to her was, “And wash your face before you sit down.” She was busy putting steaming food into bowls and had barely looked around when Sophie came up to her. Sophie went into the bathroom, picked up the damp towel someone had left in a wad on the sink, and quickly ran it over her mouth. Then she took her place at the table. She didn’t bother to sulk because she knew it wouldn’t do any good. No one in her family paid any attention to heavy silences and dark looks.

Especially not at dinner. They were all too busy spinning the lazy Susan in the middle of the kitchen table around and around, grabbing food. Sophie took a hamburger and carefully piled on a generous amount of onions, ketchup, relish, and mustard. The minute she took her first bite, a good-sized glop of it fell out onto her lap. She quickly scooped it up with her finger and put it in her mouth before anyone could notice.

Thad was telling their father about the goal he’d scored in a soccer game that afternoon. He kept jumping out of his chair and making lunging moves to show Mr. Hartley exactly how he’d saved the day. Every time he hopped up, Mrs. Hartley told him automatically to sit down. Then she’d get involved trying to keep Maura from smearing more squash all over her face and Thad would hop up again.

All the action made it possible for Sophie to sneak another handful of French fries without her mother noticing. When her belly felt as if it was about to explode, though, and she had to unbutton the top button on her shorts to make room for dessert, she started feeling sorry for herself again. She was glad her mother hadn’t nagged her, but it would have been nice if she’d showed a tiny bit of sympathy, knowing how cruel Mrs. Ogilvy had been to her that afternoon.

As usual, though, Mrs. Hartley was occupied with Maura.

Not for the first time, Sophie wished her mother would stop paying so much attention to Maura and pay attention to her. It wasn’t that Sophie didn’t love Maura—she did. She loved to play with her and watch her while she took her bath. She especially loved to be the first one into Maura’s room when she woke up from her nap; Maura always looked so grateful. Sophie knew Maura was glad to see anyone who was going to lift her out of the prison of her crib, but deep inside she couldn’t help but think that Maura was just a little happier to see her.

Mrs. Hartley said she loved all her children the same, and Sophie believed her. But she certainly seemed to spend a lot more time fussing over Maura than she did over any of the others. Sophie couldn’t remember the last time her mother had wiped her chin, she thought grumpily as she watched her mother first wipe Maura’s face and then kiss it. She would have hated it, of course, but still.

All her mother ever did was say, “Sophie, you look a mess. Go wash your face.” And not very nicely, either. Thinking about how unfairly she was treated, Sophie sighed heavily, and her mother gave her a sharp look.

“What, did you eat too much again?” she asked. Sophie didn’t think her mother sounded at all sympathetic, so she didn’t answer.

“She had two helpings of French fries,” Nora piped up.

“Nora, don’t tattle,” Mrs. Hartley said automatically.

“I can eat all I want now that I’m not taking ballet,” Sophie said to Nora. She crammed two more French fries into her mouth and chewed with her mouth open, knowing it would gross her out. But Nora wasn’t watching.

“Speaking of ballet,” Nora said to their mother quickly, “if Sophie’s not going to be taking it, we’re going to have much more money. Can I have new ballet slippers? Mine have a hole in them.”

The Hartley children were all very aware of money. Mrs. Hartley worked part-time, and Mr. Hartley, who worked for a moving company, said that the furniture he had to carry was a lot heftier than his salary. And when you had five children, Mr. Hartley said, one of them always wanted something. “If I threw a peanut in the middle of the floor, you’d all kill one another trying to get it” is how he put it.

“What’s that?” said Thad, looking at his sisters with sudden interest. “Sophie bombed out again?”

“Mrs. Ogilvy said her lessons were a waste of money,” said Nora.

“Way to go, Soph!” said Thad. He rose halfway out of his seat and leaned across the table to give her a friendly punch on the shoulder.

It didn’t really hurt, and she knew he was only teasing, but Sophie said “Ouch” anyway and rubbed her arm, hoping her mother would yell at him for being mean.

She didn’t. She just said, “Sit down, Thad,” again and went on taking care of Maura.

“I need some torpedoes,” John said suddenly. They all turned to look at him. He was sitting at one end of the table, next to his father. Even with the phone book on his chair, his chin barely cleared the top of the table. “And some tanks and some bombs,” he added.

“So you’re the one who’s been adding things to my grocery list,” said Mrs. Hartley. “Only it said ‘b-o-m-s.’ I didn’t know what that meant.”

“Sophie spelled it for me,” said John.

“Sophie, really,” Mrs. Hartley said irritably. “It’s bombs! There’s a silent b! B-o-m-b-s! You should be a better speller at your age.”

“Does anyone else find this conversation as strange as I do?” said Nora to no one in particular. “My six-year-old brother wants bombs and torpedoes, and all my mother cares about is spelling.”

“And tanks,” John said to her.

“Yes, really, Sophie,” Mrs. Hartley said, as if John’s recent military mania was all Sophie’s fault. “I asked you not to encourage him.”

“He doesn’t want to do anything with them,” said Sophie.

A few weeks earlier at dinner, John had announced he wanted to join the army. It had created quite a stir. Sophie hadn’t understood what all the fuss was about.

“You don’t want to be in the army, John,” Mrs. Hartley had said to him in the reasonable voice she used when she was confident that simple logic would change one of her children’s minds. “You’d have to shoot people.”

“Not people,” John said. “The enemy.”

“But the enemy is people,” said his mother.

John had just given her a dark look that meant she didn’t understand and hunched his shoulders. “I want to for the boots,” he said.

Sophie understood immediately. As soon as they went upstairs after dinner, she fished her old rubber boots out of her closet and took them into John’s room, where he was getting ready for bed.

“Here,” she said, holding them out. “You can have these.”

“Army boots are black,” he protested as she forced them on over the slipper feet of his pajamas.

“You have to pretend,” Sophie told him firmly. “You make believe they’re black until you get the real ones.”

John had worn them ever since. To school, to bed. He even wore them in the bathtub one night until Mrs. Hartley discovered him and pulled them off, dumping water all over the bathroom floor. Even when Thad said, “Nice ducks, John,” it didn’t discourage him.

It was exactly the way Sophie was going to be when she got her tiara. She was very proud of him.

John was wearing his boots now. Bright yellow with red ducks.

“B-o-m-s,” her mother said again, shaking her head. “Really, Sophie.”

“I only write letters I can hear,” Sophie said.

“Good Lord,” said her mother, throwing her hands in the air.

“Your report card should be a real hoot,” said Nora, after which Thad snapped his fingers

and said, “Darn! There goes the spelling bee championship.”

Mr. Hartley had been sitting calmly at the head of the table with his after-dinner toothpick sticking out of one side of his mouth, listening. Now he took the toothpick out and said, “Don’t you worry about Sophie. One of these days she’ll find out what she’s all about. Then there’ll be no stopping her. Right, Sophie?”

He leaned toward her with both elbows on the table and his sleeves rolled up showing his strong arms, and winked. Sophie sat up a little taller.

It was the first thing he had said the whole meal. She knew it was only because his plate was empty and he wanted them all to stop talking and get to the dessert, but Sophie smiled back at him gratefully. Her father didn’t single her out very often, and certainly not to say something complimentary. He was a man of few words, as their mother always said. To which Mr. Hartley always replied, “It’s a good thing, too, the way people in this family carry on.”

“Well, she’d better find out pretty soon,” Nora said ungraciously. “She can’t do anything right now.”

Sophie felt a sudden rush of confidence, thinking about no one being able to stop her. And she was suddenly sick and tired of Nora acting so superior all the time. There was one thing she could do that no one else in the family could. She was going to do it now, even though it usually ended badly.

“What about this?” she said brashly. “None of you can do this.” Sophie wiggled the muscles in the tip of her nose and felt her nostrils move in and out.

Thad and Mr. Hartley could bend their thumbs back to touch their wrists, and John could fold his eyelids up so that the pale insides showed. But no one else in the family could flare their nostrils.

Mrs. Hartley said, “Oh, Sophie,” in an impatient voice, but everyone else started to laugh. It was very nice being the center of attention for a change, so Sophie did it some more. Thad and John started shouting “Ole!” as though she were a bull pawing the ground and blowing hot air out of its huge nose. Her father laughed and said, “She didn’t get it from my side of the family.”

Even Maura clapped her hands because everyone else was having such a good time.

But when Nora put her fingers on her own thin nose and said, “I’d die if my nose looked like that,” Sophie started to feel a little less pleased. And when Thad held out his napkin as if it was a cape for the bull to charge, her whole mood changed. It suddenly felt as if they weren’t laughing with her, they were laughing at her.

Before she knew it, she was crying.

“You’re making fun of me,” she wailed, pushing back her chair.

She ran up the stairs and into her room, slamming the door behind her. They were mean, she thought as she flung herself on her bed. She made loud sobbing noises for a bit, and tried to make the tears flow while waiting to hear the footsteps of someone coming up the stairs to console her. No one did, though, and her sobs were starting to sound just the tiniest bit forced, so she stopped. Two times in one day had dried her up inside.

It was really very insulting, she thought as she sat up. The sounds of life were going on downstairs as usual. She heard chairs being pushed back and dishes clinking together as they were stacked. Then the phone ringing and Nora’s voice. When she finally heard the television spring into life and realized that her father was sitting in front of it with Maura on his lap, Sophie gave up.

Here she’d had her heart nearly broken, and nobody even cared.

She went and stood in front of the mirror. In all the times she had flared her nostrils to get attention and then ended up running up to her room, no one ever came to see how she was, she thought tragically. It would serve them right if she stopped doing it. She creased her forehead and bent her mouth into several different shapes to see how sad she could look, but she soon got tired of it. Being upset wasn’t very satisfying if nobody was around to feel sorry for you.

Sophie pressed her lips together and puffed out her cheeks as far as they would go, then tried to flare her nostrils again. They didn’t flare nearly as much that way, she always noticed. She let out a little puff of air to deflate her cheeks and tried again. Her nose did rather look like a bull’s, but it was mean of Thad to say so.

The sound of footsteps coming down the hall caught her off guard. Sophie barely had time to leap back onto her bed and put on what she hoped was a pitiful expression before the door opened. It was her mother.

“Don’t bother pulling a long face with me,” Mrs. Hartley said briskly as she dumped an armful of clean clothes onto Nora’s bed. She looked at Sophie with a combination of sympathy and exasperation. “How many times have I told you? Every time you do that thing with your nose, you end up crying. If you don’t have sense enough to stop, you won’t get any sympathy from me.

“Come on and help me,” she said as she started sorting out the laundry. “I didn’t want to come up the stairs empty-handed.” Her mother held up a pair of socks. “These are yours, I believe.”

Sophie jumped up, took the socks, and stuffed them into her drawer. Then she took Nora’s T-shirt from her mother and put it into Nora’s middle drawer. Next came Sophie’s jeans and Nora’s sweatshirt. Before she knew it, helping her mother had made Sophie feel much better.

When they were finished, Mrs. Hartley sagged onto Nora’s bed and fastened her curly hair on the top of her head with a clip she pulled from the pocket of her blouse. “This is the first time I’ve had a chance to sit down all day,” she said in her good-natured way. “Now, what’s this Nora tells me about you worrying you’re not good at anything?”

Sophie sat down next to her mother and leaned against her generous side. “Mrs. Ogilvy said I was clumsy,” she said. “I heard her.” But it had already lost its sting. Having her mother to herself made Sophie feel contented.

“She said no such thing,” said Mrs. Hartley. “And it was your own fault for wearing those shoes.”

“I wish everybody would stop saying that,” said Sophie.

“Well, it’s true.” Her mother tousled Sophie’s mass of curly hair. “You’re good at putting away clean clothes,” she said.

“I don’t want to be good at that.”

“And you’re very good at making mashed potatoes,” said Mrs. Hartley. “That’s a big help.”

“You only say that so I’ll make them.”

“True, I tricked you into it at first,” her mother admitted. “But look what happened. You became good at it.”

“Who wants to be good at making mashed potatoes?” said Sophie indignantly.

“I’m sure your Uncle Ralph wishes Aunt Helen was,” Mrs. Hartley said with a laugh. “He swears he broke a tooth on the lumps in hers.”

“I still don’t like it.”

“All right, then . . . how about being kind? You’re very good at that.”

“I am?” said Sophie doubtfully.

“Yes, you are,” her mother said firmly. “I can always count on you to help me with Maura. And you’re very kind to John.” She looked at Sophie and sighed. “Sometimes a bit too kind,” she said.

“But that’s just how I am,” grumbled Sophie, “not what I’m good at. Anyway, what’s so good about being kind?” It didn’t feel like something she could brag about. She’d never heard of people giving kind recitals. Or winning kindness trophies.

It didn’t feel like anything.

“Take it from me,” her mother said in the voice of someone who knew what she was talking about. “It’s a highly underrated skill. If more people practiced being kind, the world would be a better place.”

“Is Nora kind?” asked Sophie.

“When it suits her.”

Good. That meant she wasn’t. Being kind was beginning to sound more attractive. Sophie liked the idea of being better at something than Nora was. And it was nice getting compliments from her mother. Sophie tried to drag it out a bit longer.

“It doesn’t feel like a skill,” she insisted.

“I’m afraid it will have to do.” Her mother

put her hands on her knees and pushed herself into a standing position with a small groan that told Sophie their time alone was up. “I’ve got tons more to do before I put Maura to bed.”

“Nora won’t think being kind is being good at something,” Sophie said.

“Well, it is.” Mrs. Hartley gathered up what was left of the clean clothes and started out of the room. “And just like any other skill, the more you practice it, the better you’ll become. You can start tomorrow with Dr. Holt.”

“A doctor?” Sophie said. “I’m not sick.”

“No, but Dr. Holt is. She’s the one I told you about. She’s Mr. Spencer’s mother, over on Broad Street. She’s come to stay with them for a bit. I’m going to be seeing her three times a week. You can come with me tomorrow.”

“I thought you said she was a grouchy old lady,” said Sophie.

“It’s only because she’s lonely,” said Mrs. Hartley. “If you’re kind to her, it will cheer her up. She wants to plant a flower garden, but she can’t get around anymore. Her sight’s beginning to go as well. I’m sure she’ll be very grateful for the help. Get ready for bed now.”

“Oh, all right.” Sophie gave a resigned sigh as her mother moved away down the hall. For a minute she thought about getting out a new piece of paper and starting a third list, “Things I Don’t Want to Be Good At.” But three lists were too many, even for Sophie.

Being kind might not be so bad, she thought as she pulled her nightgown on over her clothes. Her mother had told her that was how English people got into their bathing suits at the beach so other people wouldn’t see them bare. Last summer when Nora got her bra and started making Sophie turn around while she got undressed, Sophie had decided she was going to be modest, too. She had quickly discovered how convenient it was to dress and undress this way. Now if her clothes weren’t dirty, she didn’t bother to take them off. It made getting dressed in the morning a simple matter of whipping off her nightgown.

Christmas at Stony Creek

Christmas at Stony Creek Queen Sophie Hartley

Queen Sophie Hartley Princess Posey: Monster Stew

Princess Posey: Monster Stew Princess Posey and the Next-Door Dog

Princess Posey and the Next-Door Dog Princess Posey & the Tiny Treasure

Princess Posey & the Tiny Treasure Sophie Hartley and the Facts of Life

Sophie Hartley and the Facts of Life Princess Posey and the Flower Girl Fiasco

Princess Posey and the Flower Girl Fiasco Princess Posey and the New First Grader

Princess Posey and the New First Grader The Lucky Ones

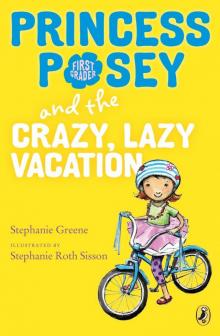

The Lucky Ones Princess Posey and the Crazy, Lazy Vacation

Princess Posey and the Crazy, Lazy Vacation Owen Foote, Mighty Scientist

Owen Foote, Mighty Scientist Falling into Place

Falling into Place Sophie Hartley, On Strike

Sophie Hartley, On Strike Owen Foote, Super Spy

Owen Foote, Super Spy Princess Posey and the First Grade Ballet

Princess Posey and the First Grade Ballet Princess Posey and the First-Grade Boys

Princess Posey and the First-Grade Boys Happy Birthday, Sophie Hartley

Happy Birthday, Sophie Hartley