- Home

- Stephanie Greene

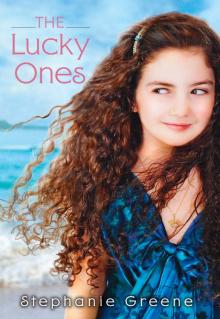

The Lucky Ones Page 7

The Lucky Ones Read online

Page 7

“Thanks, Sheba.” Their mother let go of Granddad’s arm and led Lucy over to the door as Sheba swung it open. “Would you make sure Lucy washes her hands, please. There’s no telling what germs those horrible pals of Mr. Hinton’s carry around.” She turned and beckoned to Jack and Cecile. “Come on, you two. Sheba worked hard to cook you a wonderful dinner.”

“I’ll go up and get Natalie,” Cecile said.

“She went down to the dock.” Her mother ushered Jack through the door and kept it held open. “She forgot something, so I told her she could go and get it. You go ahead and eat. Natalie can have hers later.”

“What’d she forget?” Cecile said.

“I don’t know. Come on now. Don’t keep Sheba waiting.”

“I’ll go get her.”

“Cecile!”

But Cecile was walking away on stiff, determined legs around the corner of the house. “I’ll be right back!” she cried, breaking into a run. She sped across the grass.

Natalie didn’t forget anything. She was meeting William, Cecile was sure of it. Just because she was fourteen, she was acting like she was old enough to skip dinner with the babies and meet her boyfriend. How dare her mother act as if Cecile should eat early but Natalie didn’t have to?

Cecile flew down the drive in the deepening dusk, an avenging angel. And there they were: standing together at the end of the dock with their shoulders almost touching as they watched the sun setting over the bay.

“Natalie!” Cecile shouted as she ran toward them. Natalie quickly shoved something into William’s hand as she turned around. William bent and put it on the dock behind a piling.

“What are you doing here?” Natalie said, her face tight with defiance.

“What’s that?” Cecile asked, craning to look. Whatever it was, it had made Natalie nervous. Cecile’s own nerves tingled with her sister’s alarm. Then, “You’re drinking beer?” Cecile said, incredulous.

William stepped quickly in front of it.

“It’s not mine,” said Natalie. “It’s William’s.”

“But William’s not allowed to drink either.”

“God, your sister’s a pain,” William muttered. He turned and raised his foot, bringing it down angrily on the can to flatten it. “Beer? What beer?” he said as he kicked it over the side.

“You can’t do that!” Cecile cried. “Natalie, tell him.”

“You’re the one who made him do it,” Natalie said, her face flushed. “If you’d minded your own business, he wouldn’t have.”

It seemed impossible. That Natalie would still side with him against her. “It’s time for dinner,” Cecile insisted. “Mom said to come get you.”

“Tell her I’ll be up in ten minutes.”

“She said to come now.”

They stood glaring at each other, eyes locked, the way they had when they were little. But she wasn’t going to be the one who backed down anymore; she was too old. “What else were you doing?” Cecile said accusingly.

“Nothing,” Natalie said, tossing her head.

“Nothing?” said William. “Thanks a lot, Natalie.” He grabbed her arm and started dragging her toward the edge of the dock. “I’ll show you nothing,” he said.

“Don’t you dare!” Natalie shrieked, planting her feet and straining against him. “I’ll get my hair wet!”

“Nothing, huh?” William repeated heavily.

“Kick him in the shins!” Cecile shouted.

William had to be a lot stronger than Harry to be dragging Natalie the way he was. Natalie was an expert on not getting thrown into the water. She and Cecile both were. Harry had tried a million times. Now William was inching Natalie closer and closer to the edge. His face looked positively scary: His cheeks and neck were flushed. His mouth hung open to reveal huge teeth.

Cecile grabbed Natalie around the waist and pulled.

“Let go!” Natalie’s face when she rounded on Cecile was so full of fury, Cecile dropped her hands. Natalie surged forward again, shrieking louder than before.

“Take it back,” William ordered her, his open mouth glistening. “Say you were having a fascinating conversation.”

“I was having a fascinating conversation!” Natalie shouted. She showed all of her teeth, too.

“The most fascinating in your whole life?”

“The most fascinating in my whole life!”

“All right then.” When William stopped pulling, Natalie sagged gratefully against him. She shut her eyes and put the palms of her hands against his chest, as if exhausted.

But she wasn’t exhausted at all; she’d loved every minute of it. Natalie had pretended to be weak so William would feel strong. Even more amazing to Cecile was the fact that William actually believed it. He looked so smug, so proud.

Natalie, leaning against him, watched Cecile through narrowed eyes and looked every bit as victorious.

It was all a game.

“You’re not coming up, are you?” Cecile said.

“Tell Mom ten minutes,” said Natalie.

“Tell her yourself.”

Her legs might have turned to stone, they felt so heavy. Cecile walked away from them without looking back. She heard William laugh and knew he was laughing at her. They were both laughing at her. She walked stiffly up the steps.

The sun had set. The sky was black. Cecile located the three stars of Orion’s belt and the Little Dipper above her head. A screen door slammed at the pump house. A phone rang. Fireflies flickered the length of the drive.

Why was it that sounds made at night seemed so much sharper, so much more full of significance, than those heard during the day? It was all soft, reassuring sounds when the sun was out: the faint cries of seagulls, the hum of distant lawn mowers, the heavy buzzing of bees feeding on the privet flowers.

Natalie, drinking beer. Better not to think about it. Whatever she did, she couldn’t tell her parents. There’d be a scene; scenes couldn’t happen on Gull Island. Maybe she should say she’d seen William drinking beer; that might work. Their mother would warn Natalie to be careful. Cecile felt suddenly desperate that someone warn Natalie to be careful. Quickening her pace, she shouted out with relief, “I found her!” as she rounded the corner of the house. Then, abruptly, she halted. The intensity of the floodlight in the corner was startling, yes, but it wasn’t that. Something was odd here, too.

The terrace looked empty. All of the hustle and bustle of preparing for dinner was gone. No. Someone was lying in the far, dark corner on Granddad’s lounge. Cecile stood, blinking dumbly, as the reclining figure broke apart and became two.

“Where’s Dad?” Cecile said in confusion when she saw who it was.

“Is something wrong?” King’s arm slid from around her mother’s shoulders as she stood up. “Is Natalie with you?” her mother said.

“She’s at the dock.” Cecile couldn’t stop her eyes from darting between her mother and King; they had a life of their own. “Where’s Dad?” she cried.

“For heaven’s sake, Cecile. You made it sound as if something terrible had happened.” Now that her mother wasn’t worried, she was impatient. “Your father’s inside. What difference does it make?”

“But what were you doing?” Cecile said. “What’s King doing here?”

“Excuse me?”

“It’s just…I thought…” Cecile’s voice trailed off in the face of her mother’s scornful eyes. “It’s just that Dad and Granddad were here when I left,” she went on in a faltering voice.

“You’re rude.” Her mother’s voice was ice.

Cecile looked down, her face burning.

“I’m afraid I’m imposing on your parents’ goodwill again tonight and staying for dinner.” She looked back up to meet King’s kind eyes gratefully as he came up behind her mother. Another set of gleaming teeth in a huge smile. But this was King. Surely she could trust King?

“Anne,” he said quietly as he rested his hand on her mother’s arm. “It’s all right.”

“No, it�

�s not.” Her mother shook off his hand. “She was rude, and she knows it.”

“She’s only a child,” King murmured.

“I am not a child,” Cecile said.

“Then stop acting like one,” her mother said, smiling the satisfied smile of a cat who’d successfully trapped her mouse, “and go and have your dinner.”

“That’s where I was going,” Cecile said. Her hands were clenched as she walked to the door. Back stiff, she opened it and went inside. Banished, like a bad little girl, to eat with the other children in the kitchen.

But Jack and Leo weren’t in the kitchen, only Sheba. “People in this family are behaving badly,” Cecile said as she flung herself into a chair.

Sheba laughed. “You sound like your grandfather,” she said, shutting the refrigerator door.

“Well, they are.” Cecile kicked the chair legs. “Natalie’s at the dock, flirting. You might as well throw away her dinner.”

“You just hold on to yourself,” Sheba said, “and don’t worry about your sister.”

“Who says I am?”

“Nobody has to say a word.” Sheba opened the oven door and slid out a plate. “You’ve been my worrier all your life.”

“I have?”

“Since you were a tiny thing.” Sheba lifted the lid off a pot on the stove and began spooning food onto Cecile’s warm plate. “Lord, the way you used to carry on. About the snails Jack tried to take back to Connecticut in his bucket, and the fact that lobsters were still alive when I put them in the pot…” Sheba shook her head.

“I still think it’s cruel.”

“You even worried about ants,” Sheba said. “I never will forget the time you rescued a whole bunch of those ants that were ruining your grandfather’s rose garden with their tunnels and hid them in your bedroom.”

“Granddad put down ant traps,” Cecile said. “He was going to poison them.”

“Red ants were running all over the house for the rest of that summer.” Sheba chuckled. “Your grandfather was fit to be tied.”

“I didn’t get punished, though,” Cecile said contentedly. She wrapped her legs around the legs of her chair as Sheba put the plate in front of her.

“That’s because I never told anyone about the paper bag with a few red ants, as dead as doorknobs, I found in your pajama drawer,” Sheba said.

“I know.”

“You go ahead and eat now,” Sheba said, resting her hand on Cecile’s shoulder. “I hope you’re hungry.”

“I could eat a horse,” Cecile declared.

“Did you rat?” Natalie asked as she stuck her head around the edge of their bedroom door.

Cecile looked up from her book. The lamp on her bedside table was a soft spotlight in the dark room. Lucy slept soundly in shadows on the other side. “No.”

“Good.” Natalie ran across the room and jumped onto Cecile’s bed, jiggling it merrily, as if trying to coax Cecile out of her sulk. “You’ll never guess what,” she said.

“What?”

“King’s taking us on the Rammer tomorrow. I saw him and Sis downstairs.”

“Really?” Cecile shut her book and sat up.

“And look what I smuggled,” Natalie took a large white dinner napkin out from under her shirt and put it on the spread between them. She unfolded it ceremoniously, revealing treasure. A tiny jar of caviar and a stack of paper-thin crackers.

“Mom will kill you,” said Cecile.

“No one will even notice.” Natalie rocked back and forth on her bottom as she unscrewed the cap and held out the jar. “There’s tons of it down there.”

They spread the tiny eggs with their fingers, determined to ignore the sharp saltiness of a luxury their parents coveted so highly. Shouts of laughter and the clinking of ice cubes floated up from the terrace.

“Who else is down there?” Cecile asked.

“The Whites and some couple from the club I don’t know.”

Someone put on a jazz record. Cecile turned off her light and they knelt in front of the open window, pressing their noses against the warm screen, to watch.

“Sis looks tipsy again,” Cecile said after a few minutes.

Tipsy is what their mother had said Sis was a few summers ago when Sis had started shouting on their terrace one night and their father had had to walk her home.

The children had watched as Sis leaned against their father’s shoulder and yelled, “The king is dead, long live the king, the pitiful SOB!” and then laughed.

“S, O, B spells sob,” Natalie had said excitedly. “Oh, sob, sob!” The children had rubbed their fists in their eyes, pretending to cry, as they rolled on the floor. When they asked their mother about it the next morning, she said Sis had eaten something that didn’t agree with her and it had made her tipsy. The children had laughed again to hear such a silly word.

“It means drunk, you know,” Natalie said now.

Cecile stared.

“You didn’t know that, did you?”

“I did too.”

“You know what else?”

Cecile shook her head.

“That isn’t lemonade in Sis’s thermos. It’s liquor.”

Cecile was shocked. “How do you know that?”

“William.”

“What does William know?”

“We saw Sis one afternoon when she was leaving the beach. William could tell she was drunk.”

“It’s none of William’s business,” Cecile said. Then, in spite of herself, “Did you get drunk on that beer?”

“Don’t be an idiot,” Natalie said, jabbing her.

“Don’t you be an idiot,” Cecile said, jabbing back. “What does drunk feel like, anyway?”

“Sob, sob!” Natalie joked, rubbing her eyes.

Her sister’s laughing face was so close, her friendly glance so familiar, Cecile didn’t ask how Natalie could bear him. She looked out at the party; she didn’t even want William in the room.

Chapter Eight

“Model walk,” Natalie commanded.

Cecile took one of the towels she and Natalie were carrying down to the dock and carefully balanced it on her head. Keeping her back stiff and her eyes straight ahead, she walked as steadily as she could, the way models walked on runways in fashion shows. She and Natalie used to practice at home using books. On the Island, they used towels and had contests to see who could make it down to the dock without losing theirs.

With their colorful towels piled high, their arms laden with canvas bags and more towels, they could have been the leaders of a caravan crossing the desert. Lucy and Jack had run on ahead with their father. Their mother and Granddad were bringing up the rear.

The drive was warm beneath Cecile’s feet; the hamper banged rhythmically against her legs. “Mom said we’re having lunch at the Hungry Pelican again,” she said over her shoulder. She pictured the white stucco restaurant perched on the hillside above the bay and the tall foamy drinks with umbrellas King had ordered for them last year. “King said he bought bigger inner tubes. I can hardly wait to ride them.”

When her towel threatened to slip to one side, Cecile tilted her head. To be going out on King’s boat at last! She’d stand in the bow as they roared into the bay and pretend to be the masthead, holding her face into the wind as they cut across the water. Waves would part helplessly under the bow while small boats zigzagged ahead of them. When the sun got too hot, she’d sit under the awning and watch her father, Granddad, and Jack fish.

She was so busy picturing the day that when she reached the top of the stairs and saw the boy standing with his back to her at the entrance to the boathouse, she halted. He jabbed a metal scoop into the ice cooler, again and again, and let the cubes clatter into one of the two buckets at his feet. The other bucket was full.

One last scoop and the second bucket was full, too. The boy tossed the scoop into the cooler and let the lid slam shut. Cecile saw the muscles in his arms flex as he bent down and picked up a bucket in each hand. She could count

the ribs in his tanned, shirtless back. Her heart was pounding in her ears, as if something had leaped out at her in the dark and terrified her.

“Don’t stop here,” Natalie said impatiently as she came up behind. “Nobody can see where they’re going.”

“Sorry.”

The boy glanced their way as he turned. His eyes slid over Cecile as if she weren’t there and rested, for a fraction of a second, on Natalie, before he walked away. She might have been a ghost, the way he’d looked through her, Cecile thought, but he’d seen Natalie. And when they got on the boat, Natalie would see him. A surge of jealousy so strong she thought she might get sick surged through her. And of her own sister.

“Get going,” Natalie said, prodding her in the back.

Ahead of them, the boy jumped nimbly onto the deck of the Rammer and went below. How could she go on the boat now? Her, in her tank suit, next to Natalie in her bikini. Oh, and her chest! Cecile’s towel tumbled from her head when she looked down. Maybe she could run back and get a shirt.

But if she left, she wouldn’t be there when Natalie and the boy looked at each other. Wouldn’t be there to stop Natalie from smiling and tossing her hair. To stop the boy from smiling back. The boy wouldn’t have eyes for anyone else.

The day suddenly felt excruciating.

“Cecile! Natalie! Look!” Jack waved proudly from his perch on a blue inner tube in the stern like a prince on his throne. Lucy sat next to him on an orange one, a beaming princess. “King said we can write our names on them!” Jack shouted.

The boy came up from the cabin and went to the far side of the boat. He moved slowly toward the prow, leaning over to check that everything was in order. Natalie jumped nimbly onto the deck and dumped her towels on the low table under the awning. She fell onto the couch and rested her foot on her knee, hunching over it to inspect it.

“You made me stub my toe, you idiot,” she said. She touched the bloody flap of skin dangling from the tip and winced. Pushing up her sunglasses, she leaned back and rested her foot on the edge of the table. “Why’d you have to stop like that?” she complained, shutting her eyes.

The boy had rounded the bow and was moving toward them. Cecile glanced up when he went past; he kept his eyes straight ahead as he stepped onto the dock. He nodded to Granddad and her mother as the three met halfway down the dock and kept walking. Cecile’s legs went limp.

Christmas at Stony Creek

Christmas at Stony Creek Queen Sophie Hartley

Queen Sophie Hartley Princess Posey: Monster Stew

Princess Posey: Monster Stew Princess Posey and the Next-Door Dog

Princess Posey and the Next-Door Dog Princess Posey & the Tiny Treasure

Princess Posey & the Tiny Treasure Sophie Hartley and the Facts of Life

Sophie Hartley and the Facts of Life Princess Posey and the Flower Girl Fiasco

Princess Posey and the Flower Girl Fiasco Princess Posey and the New First Grader

Princess Posey and the New First Grader The Lucky Ones

The Lucky Ones Princess Posey and the Crazy, Lazy Vacation

Princess Posey and the Crazy, Lazy Vacation Owen Foote, Mighty Scientist

Owen Foote, Mighty Scientist Falling into Place

Falling into Place Sophie Hartley, On Strike

Sophie Hartley, On Strike Owen Foote, Super Spy

Owen Foote, Super Spy Princess Posey and the First Grade Ballet

Princess Posey and the First Grade Ballet Princess Posey and the First-Grade Boys

Princess Posey and the First-Grade Boys Happy Birthday, Sophie Hartley

Happy Birthday, Sophie Hartley